Sometime in the spring of 1976 I had an occasion to ring the dept of transport in Canberra. The reason escapes me completely—probably to do with an aircraft fly over—at least something to do with approval for a 150th anniversary event.

The very first person to speak with me commenced by inquiring as to whether I was one of those peanuts in Albany attempting to get hold of the Eclipse Island lighthouse.

“No!” I replied, “But do tell me all about it”.

He informed me that the Maritime Safety Authority vessel the Cape Don was presently at Eclipse Island, just south of the heads of King George Sound.

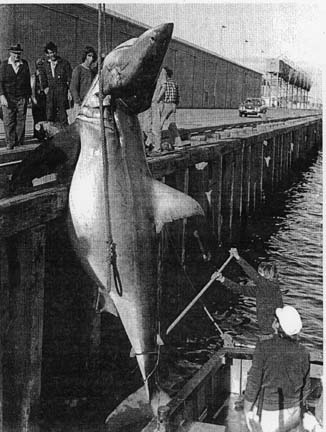

The ship’s engineers were on the island removing the 50 year old Chance Brothers kerosene lantern with its enormously brilliant prism lenses and taking it to the Fremantle Maritime Museum

And, Canberra was gifting to a Fremantle museum a lighthouse that had spent all it working life in Albany’s waters?

The town’s maritime history was going to float off to the Swan River colony’s port facility, in time for Perth’s 150 celebrations in 1979?

“Well, count me in as one of the peanuts” I shot back, adding “and to whom do I need to speak to pursue this matter?”

The public servant informed me that the Fremantle deal had been struck a couple of years ago; there was no way Albany was going to get Canberra to budge; and I would need to speak with his boss to take it further.

He then kindly put me through to his superior who also told me the same; that the agreement with Fremantle was water-tight and I would need to speak with his boss to take it further. And similarly he saw to it that I was progressing rapidly up the chain of command.

By now I must have been speaking with a level 6 in the national capital, same story, plenty of tut-tutting along with no! no! no! But if I wanted to speak with the head of department I would need to ring back the following morning.

Late that afternoon I went looking for the blokes removing the lighthouse and chanced upon the engineers from the Cape Don, slaking their thirst in the front bar of the Royal George Hotel.

The maritime engineer John Lemon (a really good bloke) bet me his ‘lefty’ as a guarantee we would not be successful in getting the lighthouse off-loaded in Albany the next day. Like, we were really up against it, for the job would be completed by noon the following day with the vessel heading straight to Fremantle. Lemon did however give me the dimensions and weight details of the cargo in the unlikely event the vessel pulled into Albany.

Bright and early the next day I was on the phone once more to Canberra, seeking approval from a real bigshot in the Maritime Services Dept. He was a kindly man and expressed a good deal of interest in Albany’s 150th celebrations. This was a bigwig from the national capital showing a genuine regard for the great southern community.

“You know’ he said, “I actually went to high school in Albany”

My riposte was “there’s no more compelling argument that you need to send a telegram to the master of the Cape Don and instruct him to drop the lighthouse off in Albany this afternoon?”

Shortly afterwards at around 11am I did as the bigwig instructed and went to the Albany Port Authority and spoke with the master of the ship by radio to confirm that he had received the telegram and find out when he planned to dock.

My staunchest ally mayor Harold Smith was away at the time and I need approval to get 2 semi-trailer trucks from Bell Bros down to the port by 2pm. So I sought the ok from his deputy ‘Noddy’ Richards who initially balked at any expenditure without council approval, but concluded by saying “thanks for nothing—-see you in gaol—-you better get the trucks!”

Mid that afternoon the master of the Cape Don off loaded many tons of valuable Eclipse Island lighthouse equipment, packed in boxes and had me sign a receipt on his manifesto.

Payment involved a couple cartons of beer stubbies for the crew and engineer John Lemon and in gentlemanly manner I forgave him the bet involving any anatomical parts.

Footnote:

Saving the Eclipse Island Lighthouse took less than 24 hours and the luck of coming across a former Albany student to snare this prized possession. Sadly those crates offloaded that day languished at the back of the town council depot for a decade or more before it was finally re-erected to pride of place in the Residency Museum.